When the name Jean Luc Godard is uttered, this never goes without praise. He played an important part in the emerging of the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague) and therefore his name is among the list of directors that you need to have seen one or two films of if you want to count in film discourse. My first Godard was Le Mépris (3,5*) followed by Vivre sa vie (4*). Today I want to write about arguably his most important film, À bout de souffle.

This film is essentially the foundation of the French New Wave, characterized by the shaky film technique, fragmentation, jump cuts and existential themes. What directors wanted to convey with this movement was that you are in first place watching a movie and that this should be clear. They were against the dream-like world of Hollywood with its clear plot and linear narrative and fabricated dialogue. In first instance, this movement was pioneered by film critics who had no filmschool background. They stressed the importance of the signature of the ‘author’ to be visible.

Perhaps this influenced Derrida in his notion of the signature (he believed that someone puts their mark on their work and this work starts living on and on in the absence of this author, so the thing that is most important is the absence of the author.) The spectator and director keep missing each other. The spectator is absent at the moment of shooting while the director is absent at the moment that the spectator views the movie. That is why the spectator can give her/his own interpretation of the movie rather than have it be fabricated already by the director.

Though the aim of French New Wave was to keep this signature in the movie, for the director to always be present rather than live in the shadows of the film. This started a trend of cinema-enthousiasts to speak in terms of directors rather than film titles. You know when a movie is typically Lynchian or Tarantino-esque. But that is because they have a huge list of movies and they are all coherent in their ways of linking to the director. This is the ‘sign’ of Derrida. It is something that is repeated over and over again (because if you only see one movie by a director, you cannot speak of something being typically Lynchian as you have no frame of reference.)

What the movie tries to do is pretty straight forward. The shaky shots slap you in the face with the realization that you’re sitting there watching a movie. What I found interesting were the Hollywood references. The male protagonist, Michel, is borrowing his style from Humphrey Bogart. I have a feeling that Godard did this to poke fun of how we get sucked into the dream of Hollywood that we start believing we can become the people on the screen. We strive to be Humphrey or Rita because the characters they portray in movies are generally sympathetic. In French New Wave movies you don’t aspire to be the protagonists, rather you are them. Because they are human with their flaws and quirks. Michel is an asshole. The balancing act is Jean Seberg as Patricia who’s not afraid to call out Michel on his misogyny and hastiness.

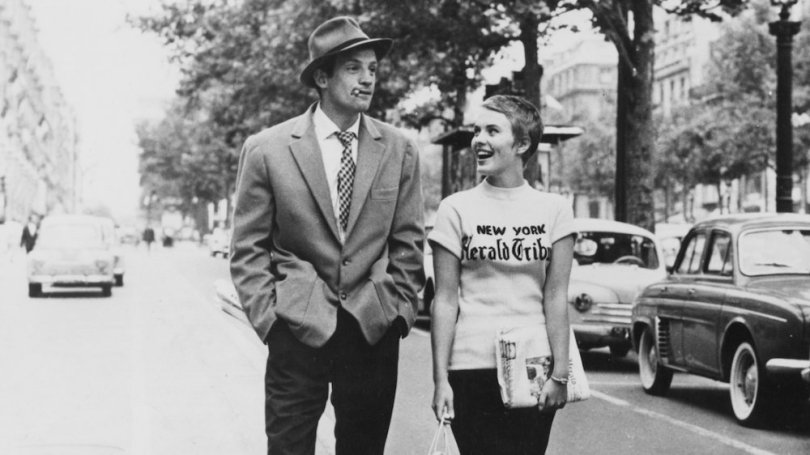

Michel kills a police officer as he’s being followed while driving a stolen car. He tries to flee the country but not without Patricia, an American journalist he’s met a few times. The movie follows him trying to persuade her as she is showing signs of doubt. She tries to prove that she doesn’t love him, both to him and to herself which ends on a noir-esque note.

From the beginning I knew I’d strongly dislike Michel. I am not sure if Godard liked the character or not but he did not seem to have any redeeming characteristics. I did like Patricia as she showed a certain independence that is hard to find in movies of that era. We see women that appear as these strong and calculated but always in relation to a man. Patricia is a woman that is entirely independent and focuses on her career. She is introduced in the movie as she distributes American newspapers in the streets of Paris. We see her as she meets several men in a work setting and she has heavy discussions with them about love, sex, soul and the role of women in society while at the same time trying to find love. As much as Michel tries to tell her he loves her, he only does it selfishly and conditionally. We see before them that both of them are not really in love, just hopeless in their pursuits. It then comes as no surprise that Patricia realizes she doesn’t love him and she has an important decision to make.

I sadly didn’t love this movie as much as I should seeing the way Patricia was portrayed and the ending. She deserves every star I can give. The movie just falls flat at certain points. The way it was shot didn’t really bother me, which seems to be an issue for many other people. For how revolutionary this movie, as uninteresting it was to me at times. So while I understand the movie in its context, I have to hold it to the same standards I do other movies. I can’t exactly pinpoint the exact reasons why I didn’t like it, maybe I’m just holding it to the same standards as Vivre Sa Vie which was topically way more gripping. So historical background aside, this movie nothing spectacular for me. If only the main character was more like Humphrey maybe I could have liked it more. I can definitely appreciate the feminist context of it, though.

Final verdict: 3* (all for Jean.)

Really nice review and interpretations 🙂 I knew French New Wave only in name and not much else so I found it really interesting to read your thoughts.

LikeLike